In the mountains of medieval Japan, a Zen monk named Ryōkan wrote:

In my hut this spring,

There is nothing—

There is everything!

Half a world away and two millennia earlier, in a garden in Athens, Epicurus taught:

"Nothing is enough for the man to whom enough is too little."

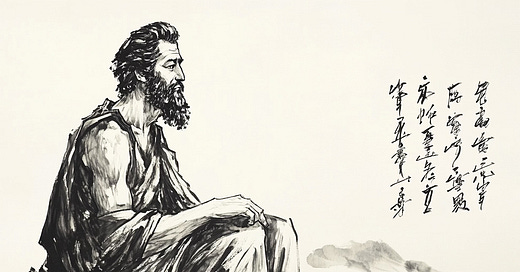

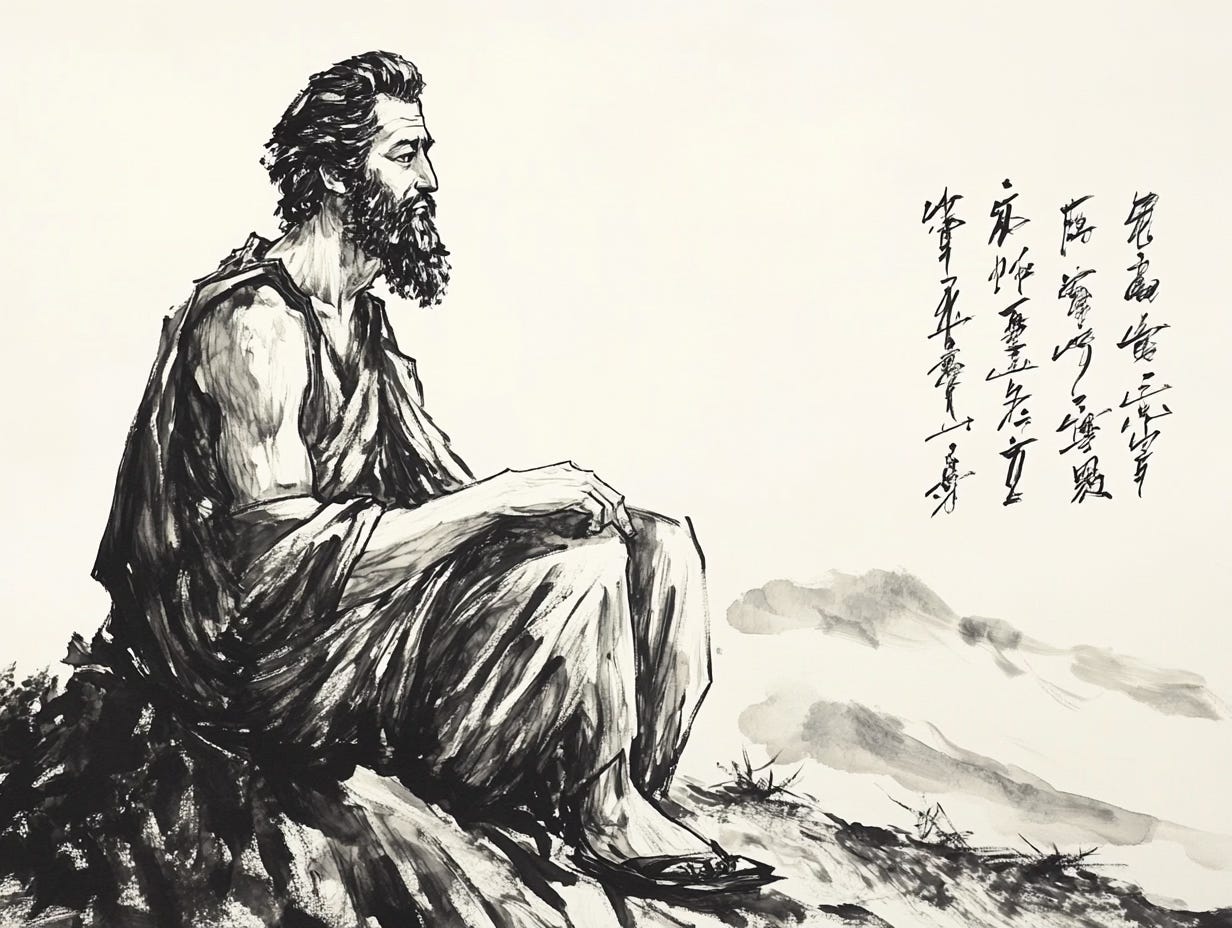

These two sages, separated by vast distances of time and space, discovered remarkably similar truths about the path to contentment. While one wrote in elegant brush strokes and the other in careful Greek prose, both pointed to a profound reality: the sweetest joys are often the simplest.

The Poetry of Simple Living

Ryōkan, known as the "Great Fool," lived in a tiny mountain hut called Gogō-an. He spent his days practicing meditation, writing poetry, playing with village children, and begging for his daily food.

When a thief broke into his hut one night and found nothing to steal, Ryōkan reportedly ran after him with his blanket, calling out, "You forgot this—I want you to have it!" The thief later became his disciple.

Epicurus, though operating a school rather than living as a hermit, advocated for similar simplicity. His Garden was no luxurious estate but a modest community where friends gathered to philosophize, share simple meals, and cultivate their own food. He taught that natural wealth is both "limited and easy to acquire," while wealth imagined by vain ideals "extends without limit."

Finding Peace in an Anxious World

Both teachers recognized that human suffering often stems from our own minds rather than external circumstances. Epicurus developed his philosophy of ataraxia—freedom from disturbance—as an antidote to anxiety about death, divine punishment, and social status.

He wrote, "Don't fear god, don't worry about death; what's good is easy to get, and what's terrible is easy to endure."

Ryōkan's Zen practice similarly aimed at liberation from mental disturbance, though through different means. His poems often capture moments of pure presence:

The thief left it behind:

the moon

at my window.

The Heart of Community

Perhaps most strikingly, both teachers emphasized the importance of human connection. Epicurus declared that "of all the things that wisdom provides to help one live one's entire life in happiness, the greatest by far is the possession of friendship." His Garden was built around the cultivation of philosophical friendship.

Ryōkan, despite his hermitage, maintained deep connections with his community. He played games with children, shared sake with farmers, and wrote touching poems about human relationships. When a mother brought him her dead child's clothes, he wrote:

If I had known

How deeply it would pierce

My heart to see

These baby clothes,

I would not have agreed to keep them.

Different Paths, Similar Destinations

Yet for all their convergences, these teachers approached life's great questions from distinct angles. Epicurus built his philosophy on atomic materialism, arguing that understanding natural causes could free us from superstition. Ryōkan's Zen Buddhism, by contrast, pointed to the fundamental emptiness of all phenomena:

The water of the valley stream

Never shouts at the tainted world:

"Purify yourself!"

But naturally, as it is,

Shows how it is done.

What emerges from studying these two sages is not just their differences but their remarkable harmony in pointing to life's essential truths: that contentment comes not from having more but from wanting less, that peace is found in the present moment, and that human connection matters more than material success.

As we navigate our own complex modern lives, perhaps we can learn from both the Greek philosopher and the Zen monk—finding wisdom in their shared understanding that the path to happiness often leads through simplicity, presence, and genuine human connection.

Ειρήνη και Ασφάλεια

Peace and Safety