Thomas Moore’s "The Epicurean" Won’t Teach You Anything About Philosophy

But It Reveals Something Else

I. Introduction: A Philosophical Contradiction

Thomas Moore’s The Epicurean (1827) follows Alciphron, an Athenian philosopher leading the Epicurean Garden, as he abandons his school’s teachings to pursue immortality in Egypt. Set in the 3rd century CE, the novel blends Egyptian mysticism with a Christian conversion arc, reflecting the 19th century’s fascination with antiquity and spiritual yearning. Alciphron’s journey—marked by fear of death and mystical questing—directly contradicts the philosophy he claims to champion, revealing less about Epicureanism than about Moore’s own perspective on the era he lived in.

The novel’s popularity stemmed from its exotic setting and Romantic sensibilities. Yet its true significance lies in its unintentional exposure of early 19th-century anxieties: the tension between Enlightenment rationalism and the persistent hunger for transcendence. Moore’s flawed portrayal of Epicureanism becomes a mirror for his contemporaries’ struggle to reconcile reason with faith.

II. Thomas Moore: Between Worlds

Thomas Moore (1779–1852) navigated multiple identities: an Irish Catholic writing for Protestant Britain, a nationalist poet embraced by London’s elite, and a man of faith skeptical of dogma. Born in Dublin during anti-Catholic penal laws, he balanced Irish pride with pragmatism, crafting works acceptable to British audiences. His Irish Melodies—lyrics set to traditional airs—romanticized Ireland’s plight while avoiding overt politics, a tightrope act that secured his fame.

Moore’s religious views mirrored this duality. A lifelong Catholic, he rejected institutional authority in favor of personal spirituality. The Epicurean reflects this ethos, framing faith as an individual journey rather than promoting doctrinal submission. Written during a period of rising secularism, the novel defends spiritual experience against materialist philosophy—yet ironically ignores the actual tenets of Epicureanism. His character Alciphron’s conversion critiques materialism but substitutes emotional appeal for philosophical rigor, a telling omission.

III. Romanticism’s Reinvention of Antiquity

The Romantic era (~1800–1850) reimagined classical antiquity as a wellspring of mystery rather than a model for imitation. Egypt, popularized after Napoleon’s 1798 campaign, became a symbol of esoteric wisdom—a counterpoint to Enlightenment rationality. Moore’s novel exploits this fascination, positioning Egypt as a realm where spiritual seekers might transcend logic through mystical revelation.

Romantics often reduced ancient and foreign cultures, like the mysterious Egypt, to aesthetic motifs. Moore treats Epicureanism the same way: romanticizing its celebration of beauty while ignoring its rigorous physics and ethics. His Alciphron embodies this selective approach. As leader of the Epicurean Garden, he should exemplify its rejection of superstition and acceptance of mortality. Instead, he abandons everything after a prophetic dream and goes to Egypt, chasing the very immortality Epicurus dismissed as folly.

Moore’s Egypt and Epicureanism share a key trait: they are extinct. This distance allowed him to critique 19th-century Christianity indirectly. By setting his story in a vanished world, he could explore spiritual alternatives without threatening contemporary norms—and revive that world in a vision of his own making.

IV. Epicureanism: What Moore Got Wrong

Moore’s tale is presented through a frame of a 19th person discovering an ancient scroll upon which is written the story of Alciphron, a fictional leader of the Epicurean school. The Garden that Epicurus founded had become the grandest of all the ancient schools with its modest grounds having expanded to their zenith by the reign of Valerian in Rome.

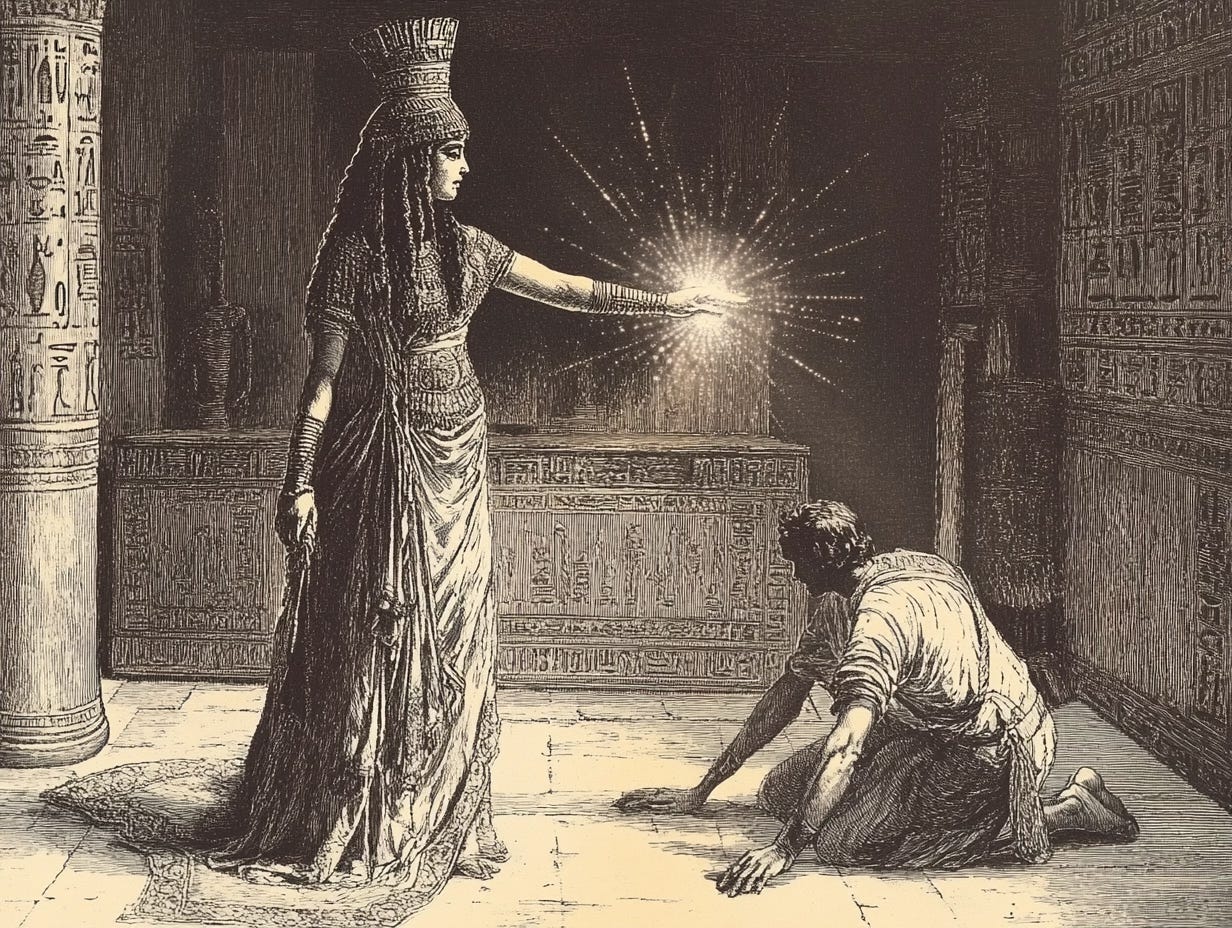

Alciphron is restless with his idyllic life because he realizes that it is finite. Hoping to find a secret to immortality, he goes to Egypt and there finds a mysterious woman who leads him on an initiation into Egypt’s deeper mysteries. Through a secret passageway– a very old story trope it turns out– he follows her into an underground world of Egyptian mythology.

The twist is that the beautiful Alethe is secretly a Christian, a member of a small and imperiled group in Egypt. Alciphron gives up everything to be with her, becoming a Christian so that they can wed. But Alethe is killed by religious bigots. In the story’s coda, we learn that all ends well for Alciphron. He suffers terribly and is humiliated and then killed. But he dies a martyr for the faith, which gives this bitter ending a sweet aftertaste, at least for believers.

As a piece of fiction Moore’s tale has a lot going for it. As a philosophical treatise and piece of Christian apologia, it’s got some serious problems.

To grasp the depth of Moore’s misrepresentation, we must first understand authentic Epicureanism. Founded by Epicurus (341–270 BCE), this philosophy combined atomistic physics with a therapeutic ethics aimed at ataraxia—tranquility through freedom from fear. Its core tenets included:

Materialist Reality: The universe consists of atoms and void; no gods or spirits intervene.

Mortal Soul: The soul dissolves at death, making fears of divine punishment irrational.

Pleasure as Peace: Happiness stems from avoiding pain, not indulging senses.

Rejection of Superstition: Natural phenomena have natural causes.

Withdrawal from Public Life: Focus on friendship, avoid political strife.

Epicurus distilled these ideas into the tetrapharmakos (“fourfold remedy”): gods pose no threat, death is harmless, pleasure is easily attainable, suffering is manageable.

Moore’s Alciphron violates every principle. As leader of the Epicurean Garden, he obsesses over immortality—the very fear Epicurus sought to cure. He chases Egyptian mysticism, credits divine intervention for surviving a storm, and abandons reason for revelation. A real Epicurean would sooner renounce philosophy than embark on such a quest.

This disconnect suggests Moore relied on stereotypes of Epicureanism as hedonism rather than studying surviving Epicurean texts. The novel’s hero ignores atomism, therapeutic ethics, and anti-superstition arguments. “Epicurean” becomes a label for “materialist in need of saving,” stripped of its philosophical depth.

One charitable reading: Moore might be critiquing later Roman-era Epicureans, whom Alciphron claims corrupted the school’s simplicity with lavish banquets. Yet even this fails—Alciphron shows no grasp of basic Epicurean tenets.

V. Alciphron: A Leader Who Never Led

Alciphron’s contradictions defy belief. At 24, he leads the Athenian Garden—a role requiring decades of study—yet embodies none of its teachings. Imagine an astronomer who goes on a mystical journey and falls in love only to end up worshipping the sun.

These contradictions raise the question of Moore's intentions. Is he treating Epicureanism ironically, creating a fictional leader who doesn't believe in its dictates and acts contrary to its lessons in order to show how hollow its values really are? This reading has some merit, as it would serve Moore's apparent goal of showing the inadequacy of materialist philosophy.

However, the characterization of Alciphron doesn't support this interpretation. He seems genuinely conflicted when he pretends to convert to Christianity for Alethe's sake, suggesting a character with authentic philosophical commitments rather than a caricature designed for easy dismissal.

More likely, Moore simply didn't have a deep understanding of the ancient creed and chose it primarily for aesthetic reasons. There are virtually no references to Epicurean physics or ethics anywhere in the text.

Alciphron never considers the atomic theory that underpinned Epicurean materialism, never reflects on the nature of pleasure as freedom from disturbance rather than sensual indulgence, and never employs the therapeutic arguments against the fear of death that were central to Epicurean practice. If Alciphron wrestled with these but still found them wanting, we’d have a richer character psychologically.

VI. When All Gods Are Real: Moore’s Unintended Pluralism

Just as Epicureanism is chosen for its aesthetic qualities, Egypt is likewise painted with a Romantic veneer. But in reviving Egypt’s mysteries for the sake of his story, Moore stumbles into a problem.

As the novel progresses, it reveals layers of theological contradiction that Moore himself seems not to have recognized. These unintended ironies create fascinating tensions within the narrative's metaphysical framework and ultimately undermine its apologetic purpose.

Alciphron’s journey into an Egyptian pyramid reveals a literal underworld teeming with gods and magic—a realm presented as objectively real, not metaphor or trickery. Later, Christian hermits teach him their miracles surpass these “pagan” wonders. But if both faiths produce supernatural results, how does one choose?

This isn’t just a plot hole—it’s a crisis of logic. Moore assumes Christianity’s superiority but offers no criteria to judge competing revelations. Alethe, the Christian priestess, worsens the problem: she abandons Egyptian gods after witnessing their power, swapping one mysticism for another. Alciphron, meanwhile, shrugs and follows her lead, casting off a “false” world of religious mysteries for another “true” one.

Moore’s goal—to champion Christianity over materialism—backfires. By validating multiple supernatural systems, he accidentally argues for religious relativism. The irony mirrors his own life: an Irish Catholic in Protestant Britain, straddling worlds where neither side held monopoly on truth.

VII. Into the Pyramid

Moore’s choice to send an Epicurean into a pyramid isn’t random—his journey is an intentional nod to the one that Plato supposedly took. Stories of Plato learning Egyptian mysteries had been rediscovered centuries before Moore and promoted by the Neo-Platonists, an intellectual wave that sought to meld Platonic ideas with occult and mysticism. Epicurus, incidentally, was opposed to Plato and tried to counteract his idealism with his own materialist rationalism.

By plunging Alciphron into the pyramid, Moore flips the script. He drags materialism’s poster child back into mysticism, rejecting Enlightenment rationality. Moore’s mashup of rivals (Plato vs. Epicurus, reason vs. mysticism) creates philosophical soup, but his aim is clear: romance over reason, inspiration over logic.

This confusion of rival philosophies further suggests Moore’s thin understanding of both. Accuracy mattered less than symbolism. Alciphron’s journey isn’t about ancient debates but 19th-century ones: a plea to feel instead think, believe instead of doubting. All things an Epicurean would scoff at.

XI. Conclusion: The Accidental Truth-Teller

The Epicurean fails as philosophy but succeeds as cultural archaeology. Moore’s missteps—Alciphron’s incoherent Epicureanism, the unresolved clash of Christian and Egyptian miracles—unintentionally expose early 19th-century anxieties. The novel is less about ancient Athens than about Romantic Europe’s struggle to reconcile reason with faith, progress with nostalgia.

Yet there’s a final, profound irony Moore was definitely not aware of. The persecuted Christian sect that moves Alciphron—humble under Valerian—would, within centuries, wield imperial power to suppress Epicureanism and all rival philosophies.

The faith he embraces as liberating would become the very force that erased his intellectual heritage, replacing Epicurus’ celebration of pleasure with puritanical dogma. Moore romanticizes the Garden in full bloom while crafting a love story with the ideology that would salt its earth. His Alciphron abandons rationality for a creed that later condemned free thought as heresy, exchanged atomism for original sin, and traded therapeutic ethics for eternal damnation.

The Epicurean thus becomes a double tragedy: a requiem for a philosophy Moore misunderstood, and an unwitting ode to the forces that buried it. In bending history to serve Romantic spirituality, Moore’s novel about an ancient scroll rediscovered from the past becomes an unintentional palimpsest. The story not only obscures everything about its titular philosophy but becomes a love letter to the very creed that buried it.

Ειρήνη και Ασφάλεια

Peace and Safety

„Imagine an astronomer who goes on a mystical journey and falls in love only to end up worshipping the sun.“ 😂 that's brilliant

Thanks, Matthias! I’m proud of that one. It took a lot of bad metaphors before getting to that one.